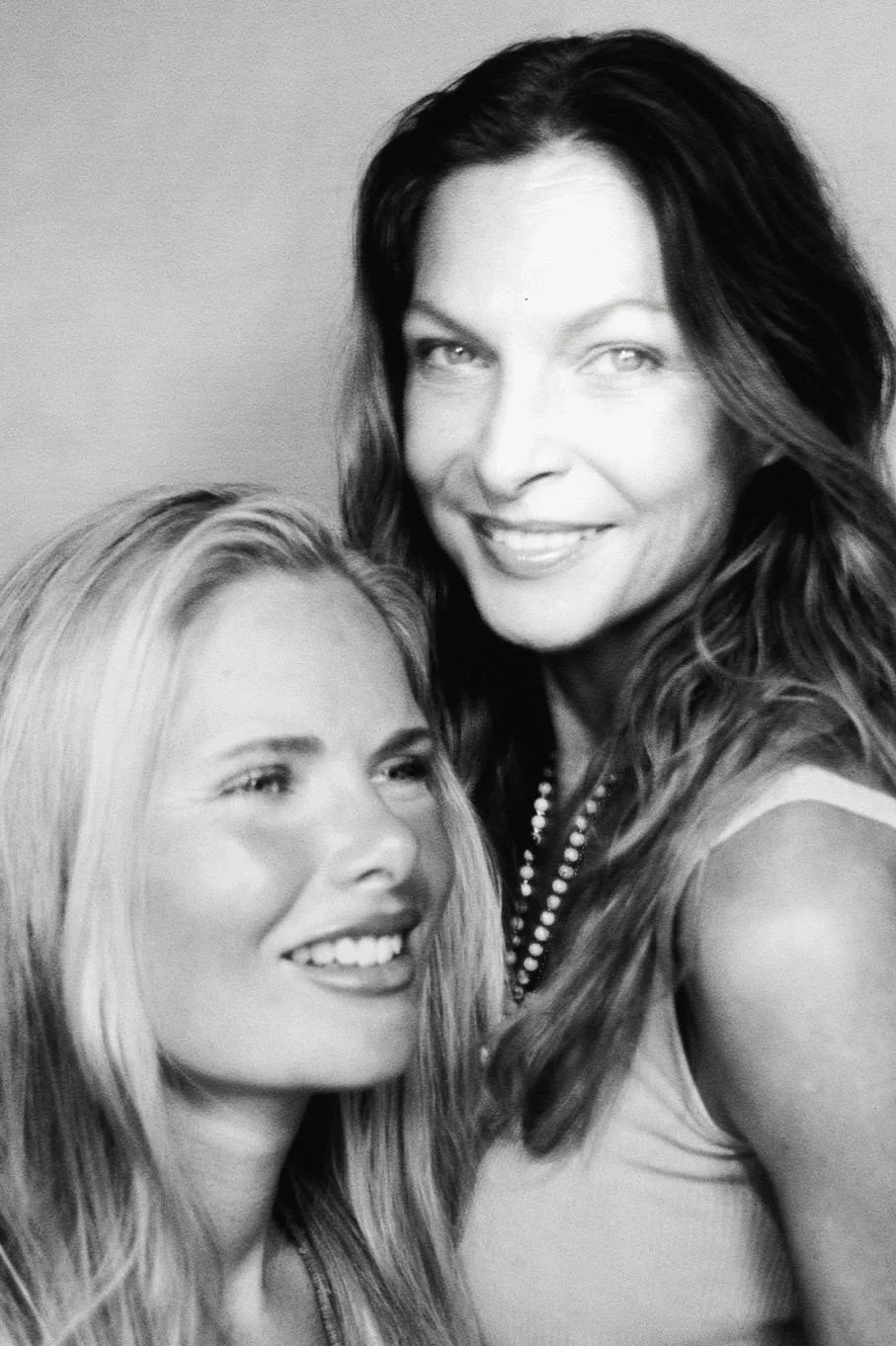

Strand by Strand: How Ibiza-based artists Aline de Laforcade and Maija Carr have woven their distinct heritages into a cool and contemporary craft revival.

By Maya Boyd

On the northern edge of Ibiza, tucked between the pine forests and fields of San Mateo, sits a whitewashed house filled with rope, reeds and coils of cotton. Sunlight falls in shafts across unfinished chairs, their wooden skeletons awaiting new skins of fibre. Skeins of hemp hang from beams like drying herbs. The air carries the mixed scents of salt, dust and resin. This is where two artists - Aline de Laforcade and Maija Carr - spend their days side by side, weaving and reweaving, their hands in near constant motion.

Their practice is rooted in an ancient craft and yet determinedly modern, caught between tradition and invention. It is a dialogue between heritage and rebellion, instinct and structure, between two women who came to weaving by very different roads but who have found, in each other, a vital counterpoint.

““I am from everywhere and nowhere,” Aline says, her voice steady but carrying the weight of distance. “From my birth in Beirut, I kept moving - Saudi Arabia, Australia, New York, Paris, London, Brussels, Monaco. When I arrived in Ibiza in 2010, I said, ‘How come nobody told me about this place?’ Because I felt this island had everything of me.” It is a declaration that encapsulates her: an artist shaped by displacement, heritage and contradiction. She comes from an old-school, aristocratic French family, yet spent years in New York’s East Village as part of the underground psychedelic scene while running several businesses and working in the arts. “I had grown weary of refinement so overwrought and performative that it ultimately lost its true elegance,” she says. “I longed to strip life back to its essence, where I discovered a sense of freedom and liberation.”

That hunger for the elemental is what led her, by chance, into weaving. “I’d always used my hands to create, but weaving unlocked a flow I’d never experienced before, and it became my authentic, intuitive, silent language,” she says. “Through it I merge timelines, bringing primitive history into the contemporary world, because the process itself encapsulates the roots of humanity. In this digitalised world, we are drawn to our ancestral origins.”

As a child Aline was captivated by Mad Max, its post-apocalyptic survivalism, its insistence that humans must relearn lost skills. That fascination translated into practice: self-taught weaving, raw materials, a primitive frame loom. “It allows me to tame the materials in the way they want or need to be tamed,” she explains. “The raw fibres direct the outcome. As the textile artist Anni Albers suggested, creativity is less about imposing one’s will and more about listening to what the material itself wants to become. That’s how I work.”

Weaving, for her, is belonging - a way of grounding after a nomadic life. “It gave me roots,” she says. “It came from trying something once and never letting go.”

Maija’s route into weaving could hardly have been more different. She trained at Central Saint Martins, the crucible of British art and design, where process is as important as product. Every project had to be documented, justified, contextualised. “ We had to follow a rigorous structure: conceptualise the project during months of research, experiment with dyeing and a diverse combination of yarns and woven patterns, design the final collection and execute the project with precision” she recalls. “There was always an intricate narrative to construct, a reason why, a backstory.”

Her inspiration was often architectural: the clean rationalism of Alvar Aalto, the balance of form and function, the way structure underpins everything. Research fed into textile, design was filtered through theory, and every woven piece carried the trace of that education.

Her heritage also played a crucial role. Half English, half Finnish, Maija grew up between two worlds. She spent summers in Finland in her mother’s homeland of Ähtari, in log cabins deep in the forest where the air smelled of pine, lake water and earthy sauna smoke. “Surrounded by fir trees and an abundance of nature – Finland’s grounding essence is homogenous to Ibiza’s North,” she says. In Lapland she encountered the Sámi tribe, whose families each carried a distinct woven pattern, an identity expressed in textile. “It struck me that weaving wasn’t just functional or decorative - it was symbolic, a kind of surname.”

In the spring of 2025, Aline and Maija were among eight Balearic artists selected from hundreds of applicants through an open call to present solo exhibitions curated by CAN Art at Nikki Beach, whilst also both exhibiting at the main CAN Art fair with Eclectico Studio. Later in June, Dalt Vila–based contemporary art gallery In Between Ibiza partnered with the Giri Café, a restaurant and cultural hub in San Juan, to exhibit their works.

Maija’s collection span several series. Her Sámi-inspired tapestries, rich with carmine red and cobalt blue hues, rest alongside a woven geology of textural tapestries inspired by the Ibizan landscape. In San Mateo, she traced the geometry of rock formations and vernacular stone finca’s, translating them into woven grids of sand and chalk hues. “It was about the absence of excess as much as the presence of form,” she explains. “Light becomes a material in itself, seeping through the negative space.” This equilibrium of form and freedom is a direct inheritance from her formative years of study. “Similar to weaving on a table or arm loom, tapestry comes with certain rules you need to abide by - structures you need to follow to create a solid fabric,” she explains. “What invigorates me is knowing I can now bend those rules, shaping tactile forms entirely by hand, creating something that is both ancient and completely my own using natural materials found on the island. Tapestry has long been a language of women, passed down through generations, carried quietly across civilisations. What fascinates me is

how every country and individual culture has its own version of weaving,” Maija’s travels through Vietnam and Cambodia deepened this perspective, offering her an intimate view of traditional weaving communities, their extraordinary techniques and their inherent respect for the land. “Being immersed in those worlds gave me a profound appreciation for the lineage of craft - watching artisans carry forward knowledge that feels both sacred and timeless, while honouring fibre and natural dyeing in a way that remains inseparably tied to nature.”

Aline’s recent work marks a turning point in her practice. Over the past year, she has explored new techniques and ways of working with her materials, transforming what were once flat woven forms into soft sculptures. Her latest pieces include a work from the Fibra Domus series alongside her cocoon sculptures - dense, fibrous, and monumental - seeming to hum with a quiet, primal energy. Some hang like giant seed pods, others sprawl like ancient relics, drawing viewers into a forest of strange growths. Her explorations resonate with the raw materiality of the Catalan school of tapestry - artists such as Josep Grau Garriga, Josep Royo, and Maria Assumpció Raventós - as well as with the radical spirit of the Nouvelle Tapisserie movement of the 1960s, exemplified by Magdalena Abakanowicz, who redefined weaving as sculpture. Aline’s cocoon forms engage with a vision of femininity that is protective, animist and powerful, an alternative to conventional, sexualised notions of the feminine.

Together, their works create a dialogue of contrasts: colour and neutrality, flatness and volume, control and abandon. The show crystallises their differences while hinting at the possibility of synthesis.

Away from exhibiting, Aline and Maija’s collaborative project Woven Ibiza has taken on a life of its own. It began when Aline picked up an old Ibicenco chair, its rush weave long disintegrated, and saw not just a repair job but a vision. “The Ibicenco chair is a forgotten design icon—it deserved a rebirth,” she recalls. Aline realised that woven furniture could transcend utility and become functional art, sparking the idea for a new direction. Recognising Maija’s background in textile design, she invited her to join forces. Their collaboration brings together Aline’s conceptual imagination and Maija’s technical expertise, resulting in a practice dedicated to reviving and reinventing the island’s furniture heritage. Their chairs are at once recognisably traditional and utterly contemporary, merging local craft with fresh creative vision. While the project began with traditional Ibicenco chairs, their vision extends far beyond restoration. For Aline and Maija, any chair frame can become a canvas for weaving. Drawing inspiration from artists such as Anni Albers and the Bauhaus, as well as the geometric clarity of Piet Mondrian and De Stijl, they translate modernist and artistic ideas into woven patterns, reimagining furniture as both structure and surface, function and art.

Sustainability is central to the project, rooted in the revival of existing chair frames through the use of durable, high-quality fibres. Each piece is reimagined as a unique work, transforming ordinary chairs into singular, lasting pieces that merge functionality with artistic expression. This approach combines respect for the past with a commitment to longevity, giving familiar forms a new identity.

“It’s about preservation and respect,” Aline says. “These skills are part of the island’s identity. Once, every woman knew how to weave. We’re not inventing - we’re remembering.”

At the same time, there is defiance. “We live in a digitalised world where nothing is tangible,” Aline adds. “Weaving is rebellion against that. It’s logic, common sense, making with your hands.”

Working together has meant learning to navigate each other’s rhythms and ways of approaching a project. Both artists thrive on exchanging ideas, discussing concepts, and carrying out their own research, which often feeds into shared conversations.

Maija’s formal training in textile design brings a structured perspective to the collaboration, while Aline’s abstract vision and trust in the creative process often propel projects forward into new territory. Whereas Maija has been accustomed to extensively mapping patterns out in advance, Aline is confident that clarity often emerges through making. Over time, this balance has become a strength: a dynamic interplay between planning and intuition that shapes their joint work. “It’s like weaving itself,” Aline says. “Warp and weft. Different threads, different tensions, but together they hold.” Theirs is also a conversation between personal geographies. Maija’s Finnish roots bring a calm, centered and Nordic sensibility—light, space, abstraction. Aline, who has lived for many years in Ibiza, infuses her work with tactility, sensuality, earthiness. On an island that has long attracted artists seeking synthesis, these strands find common ground. The path ahead is both modest and ambitious. For now, the workshop in the campo hums with quiet industry. Together, they want Woven Ibiza to be recognised not only as craft but as design, as art, as philosophy. “Design is about solving a fundamental problem,” Maija reflects. “If a chair woven with rope is falling apart, how do you reimagine it so it lasts, so it becomes beautiful, something people want to both look at and use?” Aline finishes the thought: “It’s also about community. Weaving is always about threads coming together. Our collaboration is like that - two strands, different textures, woven into something stronger.”

Interview by Maya Boyd

@bymayaboyd

maya@mayaboyd.com

@alinedelaforcade

@maijachristinacarr